One of the keystone arguments that the Intelligent Design movement raises both as positive evidence of intelligence and purposeful planning in certain biological systems as well as a direct challenge to the standard evolutionary narrative is the matter of “irreducible complexity.” In short, irreducible complexity refers to a system or structure that is not merely complex, but complex in a specific way where every piece of the system has to be there and in the right place before it is functional. As one scholar puts it:

“Irreducible complexity describes a system with many coordinated parts, all of which are necessary for the function of the system as a whole.”1

In other words, you can’t build it by starting with a simpler version and slowly adding parts over time because, until all the parts are there (and put together properly) the system is non-functional. It is essentially an all-or-nothing deal. Such systems have profound implications for Darwinian evolution.

Clarifying our terms

Especially because the term is so important to the subject of intelligent design, it is vital that one understand just what it means. Indeed, critics of intelligent design often misdefine what irreducible complexity is and, in doing so, sometimes end up raising objections that don’t address the real issue. For example, famed Darwinist and apologist for atheism, Richard Dawkins, offered the following definition:

“Irreducible complexity is a phrase that’s used for something that’s alleged to be too complicated to have come about, not only too complicated to have come about by chance, everybody agrees about that, too complicated to have come about by gradual evolution, by natural selection.”2

This definition contains a very crucial error. Irreducible complexity is not claiming that the structure is “too complicated” but rather that it is complex in a specific way that doesn’t allow gradual development by natural selection. It’s not the amount of complexity but rather that particular kind or nature of the complexity that makes it irreducible. Dr. Michael Behe, the biochemist who first coined the term, explains:

“By irreducibly complex I mean a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning.”3

Mathematician and philosopher Vern Poythress elaborates:

“These systems are complex, in that they involve a number of coordinated parts. They are irreducible, in the sense that they cannot be reduced to a simpler system, by eliminating one or more of the parts, and still perform their intended function at all.”4

The systems that Behe and others raise as examples of irreducible complexity are often microscopic structures in bacteria, most famously the molecular “motor” known as the flagellum. While a marvelous piece of biological engineering, the flagellum is hardly the most complex system in all of nature. The issue, again, isn’t how complex it is but rather the way it is complex: i.e., being composed of a number of integrated and necessary parts or components that must all be present and in the right order. As Behe further explains:

“An irreducibly complex system cannot be produced directly…by slight, successive modifications of a precursor system, because any precursor system to an irreducibly complex system that is missing a part is by definition nonfunctional. An irreducibly complex biological system, if there is such a thing, would be a powerful challenge to Darwinian evolution. Since natural selection can only choose systems that are already working, then if a biological system cannot be produced gradually it would have to arise as an integrated unit, in one fell swoop, for natural selection to have anything to act on.”5

This, then, is the issue. Irreducible complexity is a problem for Darwinism because it is a kind of complexity that Darwinian mechanisms cannot explain.

Darwin and irreducible complexity

Though the term “irreducible complexity” was coined by ID theorists in the 1990s, the basic concept has been a part of scholarly opposition to Darwin’s theory since it was first formulated by him and Wallace in the 19th century. Indeed, Darwin anticipated this objection and admitted its force in “The Origin of Species”:

“If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.”6

Even today, Darwin’s defenders like Dawkins admit the truth of this assessment:

“If there is anywhere in the animal kingdom or in the plant kingdom an organ which is too complicated to have come about by natural selection then Darwin’s theory is blown out of the water.”7

Poythress explains why this is such a problem:

“Darwinian gradualism might conceivably produce a complex machine gradually, if one part produces some benefit, and adding a second part produces a greater benefit, and so on. Over a period of time, selecting ‘the fittest’ gradually weeds out everything but a system with all its parts in place. But a system with irreducible complexity does not allow gradual build-up, because the system does not function at all until all the parts are both present and in place, ready to perform cooperatively.”8

Thus, as Darwin admitted from the beginning, his theory hinges on there being no irreducible complexity in nature. Even a single definite example would, as Dawkins put it, blow Darwin’s theory out of the water.

An illustration of irreducible complexity

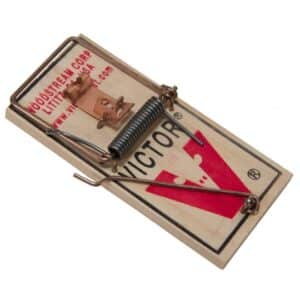

In Behe’s original book, Darwin’s Black Box, he presented what has become the go-to analogy to help explain irreducible complexity, that of the common mouse trap. You know, the kind made out of a flat, rectangular piece of wood, a spring, and a metal bar that snaps down on the mouse when the trap is triggered? While a relatively simple device (compared to, say, the phone, computer, or tablet you are using to read this article), the mousetrap is irreducibly complex because it necessarily is made of several precise parts which must all be present and in their proper place for the mouse trap to work. Consider the following parts of a mouse trap:

In Behe’s original book, Darwin’s Black Box, he presented what has become the go-to analogy to help explain irreducible complexity, that of the common mouse trap. You know, the kind made out of a flat, rectangular piece of wood, a spring, and a metal bar that snaps down on the mouse when the trap is triggered? While a relatively simple device (compared to, say, the phone, computer, or tablet you are using to read this article), the mousetrap is irreducibly complex because it necessarily is made of several precise parts which must all be present and in their proper place for the mouse trap to work. Consider the following parts of a mouse trap:

- Platform: The flat, wooden rectangle on which all the other parts rest and which gives form to the whole trap.

- Hammer: The metal bar that snaps down on the mouse when the trap is triggered and delivers the blunt force that makes the trap effective.

- Spring: The coil of metal that stores the tension that gives the force to the hammer.

- Hold-down bar: A second metal bar that runs across the hammer, holding it down until the trap is ready to spring

- Catch: A moveable, slightly hooked piece of metal that loosely holds the hold-down bar in place until it is nudged, springing the trap.

Now, all together, these parts form a simple but astonishingly effective trap. But take any of them away, and the trap is useless. Without a platform, you just have a pile of loose scraps of metal. They can’t do anything. Without the hammer, the spring has nothing on which to act. The hold-down bar has nothing to hold. There is nothing to kill the mouse. The hammer is the whole point! Yet, without the spring, there is nothing to move the hammer. The hammer can’t act on its own. It needs the tension from the spring to move it. But what holds that tension until the mouse arrives? What keeps it from springing immediately? Without the hold-down bar, nothing does. There must be a hold-down bar or you have no trap. Finally, what keeps the hammer from throwing off the hold-down bar? Or the hold-down bar from holding back the hammer indefinitely? You need a catch. You need a piece that keeps it all in place firmly enough to hold until the mouse gets there but loosely enough to let go as soon as the mouse is in place. Without every one of the parts there and in the right order, you have no mouse trap.

Could a mouse trap like this develop gradually? Could there be an earlier, simpler version with no catch? Or one with no hammer? Or one with no spring? No. The system is irreducibly complex. There is no reason to develop any of the parts until you have all of them and, even if you already have them, no reason to put any of them together unless you put all of them together in just the right configuration. Even if you argue (as some of Behe’s critics have) that the individual parts could develop on their own with completely different functions (the platform as a paperweight, the spring as maybe a weird tie clip, etc.), that still doesn’t explain the vast assembly leap wherein all those parts must come together into just the right order and shape of the mouse trap. This is irreducible complexity.

The most popular example

So, where does this show up in nature? Scholars have argued for all kinds of examples, but (as mentioned above) perhaps the most iconic, certainly the one that has received the most attention, is the bacterial flagellum. This microscopic whip-like structure on many bacteria can spin rapidly to propel the microbe wherever it needs to go. It is designed remarkably similar to an outboard motor on a boat, possessing a drive shaft, a rotor, a stator, bushings, etc. Even Richard Dawkins describes it as “A beautiful piece of miniature engineering” and notes “the remarkable thing is that is has a bearing, it has an axel, it rotates in a bearing…possibly the only example of a true wheel in the living kingdoms,”9 though, of course, Dawkins denies that even such a system is irreducibly complex.

So, where does this show up in nature? Scholars have argued for all kinds of examples, but (as mentioned above) perhaps the most iconic, certainly the one that has received the most attention, is the bacterial flagellum. This microscopic whip-like structure on many bacteria can spin rapidly to propel the microbe wherever it needs to go. It is designed remarkably similar to an outboard motor on a boat, possessing a drive shaft, a rotor, a stator, bushings, etc. Even Richard Dawkins describes it as “A beautiful piece of miniature engineering” and notes “the remarkable thing is that is has a bearing, it has an axel, it rotates in a bearing…possibly the only example of a true wheel in the living kingdoms,”9 though, of course, Dawkins denies that even such a system is irreducibly complex.

Yet, these tiny molecular motorized propellors consist of specially designed and perfectly arranged proteins put together in just the right order and sequence. As Dr. Robert P. Waltzer notes:

“If it only has some of its several essential parts, it doesn’t work as a flagellum. If one or more of these parts is a dud, or missing, the entire flagellum grinds to a halt. Or if all the parts are present and in good working order but haven’t been precisely arranged, again, the flagellum doesn’t work and instead just soaks up valuable resources from the bacterium, decreasing its likelihood for survival.”10

The point is that the right proteins must all be present and put together exactly right for the system to work. It’s all or nothing. Even if (as some Darwinists propose) some of the parts might have already existed before the flagellum with a different functional use in an entirely seperate system, Darwinian evolution still requires a slow, step-by-step process whereby those parts are gradually rearranged and numerous novel parts are developed and added in just the right place to form the flagellum. The problem is, for Darwinism to work, each of those tiny, gradual steps has to provide a beneficial function for natural selection to allow it to pass on. But they don’t. The moment you start trying to change the allegedly older, simpler system into a flagellum, whether you begin by moving one of the existing parts or by adding one of the many brand new parts that will be needed, you simply break the system. It’s useless. It’s dead weight until you have all the right parts and have moved them all into their proper places to build the flagellum. Darwinian mechanisms can’t plan ahead, so they won’t keep building useless, counterproductive structures while slowly working toward a goal. Natural selection and random mutation have no goal in mind. If it doesn’t work now, it will be discarded. Yet, as Poythress points out:

“An intelligent designer, by contrast, can construct an irreducibly complex system, because he can assemble the parts one by one by intelligent selection, knowing the end-product to which he is heading”11

Irreducibly complex systems imply planned, purposeful development. They point to a designer.

Does biblical creation require irreducible complexity?

While the concept of irreducible complexity is perfectly consistent with biblical creation, nothing in scripture demands that we find irreducibly complex structures in nature. To put it another way, a designer can construct sophisticated, irreducibly complex systems in a way that blind mechanisms cannot, but a designer is not bound to do so. All kinds of designed things are not irreducibly complex. Blankets, hammers, kitchen knives, and any number of other things we make and use regularly are intelligently designed and yet are not irreducibly complex systems. Thus, the Christian need not assume that everything (or even anything) is irreducibly complex. We can follow the evidence where ever it leads. If a system which at first seemed irreducibly complex proves not to be, no Christian need fret. Nothing in Scripture, logic, or plain common sense demands that any particular structure be irreducibly complex for Christianity to be true. We can be thoughtful, open to the evidence, and take the facts as they come.

We must keep in mind, however, that Darwinists cannot be open to the evidence on this, at least not if they are to remain Darwinists. From their perspective, there cannot be any irreducible complexity in living things. If there is, Darwinian evolution is false. Thus, they will (with sincere conviction) gravitate toward explanations that deny irreducible complexity and will do their best to make those explanations seem to be reasonable (to themselves as well as to anyone else) even if they are not, just as an atheist who believes miracles are impossible will accept objectively implausible explanations for the empty tomb and the post-mortem appearances of Jesus rather than accept the resurrection. Having a doctrine against miracles, any explanation other than a miracle becomes the more likely explanation. Having a doctrine against design, any explanation other than irreducible complexity becomes the more likely explanation. Thus, we must exercise caution and critical thinking, hearing both sides, when dealing with the confident conclusions of a Darwinist claiming to have proven that this or that structure really isn’t irreducibly complex and actually could have developed gradually, step-by-step, without planning or foresight. They need to believe that this is so. Their system depends on denying irreducible complexity far more than ours depends on affirming it.

Conclusion

Irreducible complexity refers to a system or structure that is complex in a specific way where every piece of the system has to be present and in the right place before it is functional. Such systems defy Darwinian explanation as they cannot be developed gradually, piece by piece through blind mechanisms without planning. The steps along the way would have no function, would often be harmful or at least a waste of valuable resources, and would thus be weeded out by natural selection rather than saved and built upon. Irreducible complexity is not required for divine creation or even intelligent design to be true, however, it is especially consistent with these views while being totally inconsistent with Darwinian blind naturalism. Thus, when we observe and can demonstrate it, irreducible complexity is a strong argument against Darwinism and in favor of purposeful design in nature.

References

| 1↑ | Vern Poythress, Redeeming Science (Crossway, 2006) 259 |

|---|---|

| 2↑ | https://youtu.be/PZg_9EBhMWo?t=88 (Timestamp: 1:28, Accessed 08/18/2022) |

| 3↑, 5↑ | Michael Behe, Darwin’s Black Box (The Free Press, 1996) 39 |

| 4↑, 8↑, 11↑ | Vern Poythress, Redeeming Science (Crossway, 2006) 260 |

| 6↑ | Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (John Murray, 1859) 154 in the 1988 reprint by New York University Press |

| 7↑ | https://youtu.be/PZg_9EBhMWo?t=106 (Timestamp: 1:46, Accessed 08/18/2022) |

| 9↑ | https://youtu.be/PZg_9EBhMWo?t=181 (Accessed 09/06/2022) |

| 10↑ | Thomas Y. Lo, Paul K. Chien, Eric H. Anderson, Robert A. Alston, Robert P. Waltzer, Evolution and Intelligent Design in a Nutshell (Discovery Institute, 2020) 102 |